The Extraordinary Watkin Tench

At the end of 18th century, life for the average British citizen was changing. The population grew as

health and industrialisation took hold of the country. However, land and resources were limited.

Families could not guarantee jobs for all of their children. People who were poor or destitute had

little option. To make things worse, the rate of people who turned to crime to make a living increased.

In Britain, the prisons were no longer large enough to hold the convicted people of this growing

criminal class. Many towns and governments were at a loss as to what to do. However, another phenomenon

that was happening in the 18th century was I exploration of other continents. There were many ships

looking for crew members who would risk a month-long voyage across a vast ocean. This job was risky and

dangerous, so few would willingly choose it. However, with so many citizens without jobs or with

criminal convictions, they had little choice. One such member of this new lower class of British

citizens was Watkin Tench. Between 1788 and 1868, approximately 161,700 convicts were transported to the

Australian colonies of New South Wales, Van Diemen's land and Western Australia. Tench was one of these

unlucky convicts to sign onto a dangerous journey. When his ship set out in 1788, he signed a three

years' service to the First Fleet.

Apart from his years in Australia, people knew little about his life back in Britain. It was said he was

born on 6 October 1758 at Chester in the county of Cheshire in England. He came from a decent

background. Tench was a son of Fisher Tench, a dancing master who ran a boarding school in the town and

Margaritta Tarleton of the Liverpool Tarletons. He grew up around a finer class of British citizens, and

his family helped instruct the children of the wealthy in formal dance lessons. Though we don't know for

sure how Tench was educated in this small British town, we do know that he was well educated. His

diaries from his travels to Australia are written in excellent English, a skill that not everyone was

lucky to possess in the 18th century. Aside from this, we know little of Tench's beginnings. We don't

know how he ended up convicted of a crime. But after he started his voyage, his life changed

dramatically.

During the voyage, which was harsh and took many months, Tench described landscape of different places.

While sailing to Australia, Tench saw landscapes that were unfamiliar and new to him. Arriving in

Australia, the entire crew was uncertain of what was to come in their new life. When they arrived in

Australia, they established a British colony. Governor Philip was vested with complete authority over

the inhabitants of the colony. Though still a young man, Philip was enlightened for his age. From

stories of other British colonies, Philip learnt that conflict with the original peoples of the land was

often a source of strife and difficulties. To avoid this, Philip's personal intent was to establish

harmonious relations with local Aboriginal people. But Philip's job was even more difficult considering

his crew. Other colonies were established with middle-class merchants and craftsmen. His crew were

convicts, who had few other skills outside of their criminal histories. Along with making peace with the

Aboriginal people, Philip also had to try to reform as well as discipline the convicts of the

colony.

From the beginning, Tench stood out as different from the other convicts. During his initial time in

Australia, he quickly rose in his rank, and was given extra power and responsibility over the convicted

crew members. However, he was also still very different from the upper-class rulers who came to rule

over the crew. He showed humanity towards the convicted workers. He didn't want to treat them as common

criminals, but as trained military men. Under Tench's authority, he released the convicts' chains which

were used to control them during the voyage. Tench also showed mercy towards the Aboriginal people.

Governor Philip often pursued violent solutions to conflicts with the Aboriginal peoples. Tench

disagreed strongly with this method. At one point, he was unable to follow the order given by the

Governor Philip to punish the ten Aboriginals.

When they first arrived, Tench was fearful and contemptuous towards the Aboriginals, because the two

cultures did not understand each other. However, gradually he got to know them individually and became

close friends with them. Tench knew that the Aboriginal people would not cause them conflict if they

looked for a peaceful solution. Though there continued to be conflict and violence, Tench's efforts

helped establish a more peaceful negotiation between the two groups when they settled territory and

land-use issues.

Meanwhile, many changes were made to the new colony. The Hawkesbury River was named by Governor Philip in

June 1789. Many native bird species to the river were hunted by travelling colonists. The colonists were

having a great impact on the land and natural resources. Though the colonists had made a lot of progress

in the untamed lands of Australia, there were still limits. The convicts were notoriously ill-informed

about Australian geography, as was evident in the attempt by twenty absconders to walk from Sydney to

China in 1791, believing: "China might be easily reached, being not more than a hundred miles distant,

and separated only by a river." In reality, miles of ocean separated the two.

Much of Australia was unexplored by the convicts. Even Tench had little understanding of what existed

beyond the established lines of their colony. Slowly, but surely, the colonists expanded into the

surrounding area. A few days after arrival at Botany Bay, their original location, the fleet moved to

the more suitable Port Jackson where a settlement was established at Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788.

This second location was strange and unfamiliar, and the fleet was on alert for any kind of suspicious

behaviors. Though Tench had made friends in Botany Bay with Aboriginal peoples, he could not be sure

this new land would be uninhabited. He recalled the first time he stepped into this unfamiliar ground

with a boy who helped Tench navigate. In these new lands, he met an old Aboriginal.

Mrs. Carlill and the Carbolic Smoke Ball

On 14 January 1892, Queen Victoria's grandson Prince Albert Victor, second in line to the British throne,

died from flu. He had succumbed to the third and most lethal wave of the Russian flu pandemic sweeping

the world. The nation was shocked. The people mourned. Albert was relegated to a footnote in

history.

Three days later, London housewife Louisa Carlill went down with flu. She was shocked. For two months,

she had inhaled thrice daily from a carbolic smoke ball, a preventive measure guaranteed to fend off flu

– if you believed the advert. Which she did. And why shouldn't she when the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company

had promised to cough up £100 for any customer who fell ill? Unlike Albert, Louisa recovered, claimed

her £100 and set in train events that would win her lasting fame.

It started in the spring of 1889. The first reports of a flu epidemic came from Russia. By the end of the

year, the world was in the grip of the first truly global flu pandemic. The disease came in waves, once

a year for the next four years, and each worse than the last.

Whole cities came to a standstill. London was especially hard-hit. As the flu reached each annual peak,

normal life stopped. The postal service ground to a halt, trains stopped running, banks closed. Even

courts stopped sitting for lack of judges. At the height of the third wave in 1892, 200 people were

buried every day at just one London cemetery. This flu was far more lethal than previous epidemics, and

those who recovered were left weak, depressed, and often unfit for work. It was a picture repeated

across the continent.

Accurate figures for the number of the sick and dead were few and far between but Paris, Berlin and

Vienna all reported a huge upsurge in deaths. The newspapers took an intense interest in the disease,

not just because of the scale of it but because of who it attacked. Most epidemics carried off the poor

and weak, the old and frail. This flu was cutting as great a swathe through the upper classes, dealing

death to the rich and famous, and the young and fit.

The newspaper-reading public was fed a daily diet of celebrity victims. The flu had worked its way

through the Russian imperial family and invaded the royal palaces of Europe. It carried off the Dowager

Empress of Germany and the second son of the king of Italy, as well as England's future king.

Aristocrats and politicians, poets and opera singers, bishops and cardinals – none escaped the

attentions of the Russian flu.

The public grew increasingly fearful. The press might have been overdoing the doom and gloom, but their

hysterical coverage had exposed one terrible fact. The medical profession had no answer to the disease.

This flu, which might not even have begun in Russia, was a mystery. What caused it and how did it

spread? No one could agree on anything.

By now, the theory that micro-organisms caused disease was gaining ground, but no one had identified an

organism responsible for flu (and wouldn't until 1933). In the absence of a germ, many clung to the old

idea of bad airs, or miasmas, possibly stirred by some great physical force – earthquakes, perhaps, or

electrical phenomena in the upper atmosphere, even a passing comet.

Doctors advised people to eat well avoiding "unnecessary assemblies", and if they were really worried, to

stuff cotton wool up their nostrils. If they fell ill, they should rest, keep warm and eat a nourishing

diet of "milk, eggs and farinaceous puddings". Alcohol figured prominently among the prescriptions: one

eminent English doctor suggested champagne, although he conceded "brandy in considerable quantities has

sometimes been given with manifest advantages". French doctors prescribed warm alcoholic drinks, arguing

that they never saw an alcoholic with flu. Their prescription had immediate results: over a three-day

period, 1,200 of the 1,500 drunks picked up on the streets of Paris claimed they were following doctor's

orders.

Some doctors gave drugs to ease symptoms – quinine for fever, salicin for headache, heroin for an

"incessant cough". But nothing in the pharmacy remotely resembled a cure. Not surprisingly, people

looked elsewhere for help. Hoping to cash in while the pandemic lasted, purveyors of patent medicines

competed for the public's custom with ever more outrageous advertisements. One of the most successful

was the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company.

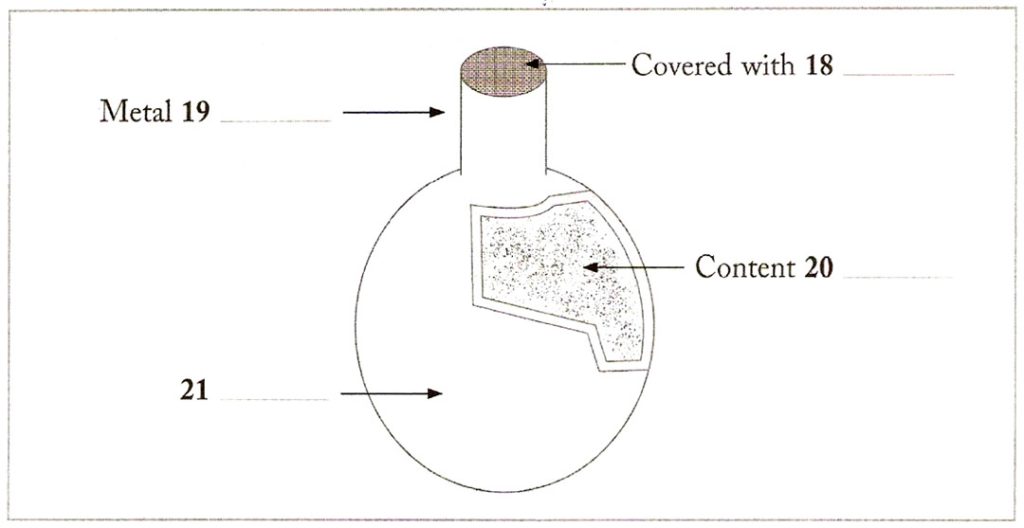

The carbolic smoke ball was a hollow rubber ball, 5 centimetres across, with a nozzle covered by gauze.

Inside was a powder treated with carbolic acid, or phenol. The idea was to clutch it close to the nose

and squeeze gently, inhaling deeply from the emerging cloud of pungent powder. This, the company

claimed, would disinfect the mucous membranes, curing any condition related to "taking cold". In the

summer of 1890, sales were steady at 300 smoke balls a month. In January 1891, the figure skyrocketed to

1,500.

Eager to exploit the public's mounting panic, the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company made increasingly

extravagant claims. On 13 November 1892, its latest advert in the Pall Mall Gazette caught the eye of

south London housewife Louisa Carlill. "Carbolic Smoke Ball," it declared, "will positively cure colds,

coughs, asthma, bronchitis, hoarseness, influenza, croup, whooping cough …". And the list went on. But

it was the next part Mrs. Carlill found compelling. "A £100 reward will be paid by the Carbolic Smoke

Ball Company to any person who contracts the increasing epidemic influenza, colds or any disease caused

by taking cold, after having used the carbolic smoke ball according to the printed directions supplied

with each ball. £1,000 is deposited with the Alliance bank, Regent Street, showing our sincerity in the

matter."

Mrs. Carlill hurried off to buy a smoke ball, price 10 shillings. After carefully reading the

instructions, she diligently dosed herself thrice daily until 17 January – when she fell ill.

On 20 January, Louisa's husband wrote to the Carbolic Smoke Ball Company. Unfortunately for them, Mr.

Carlill happened to be a solicitor. His wife, he wrote, had seen their advert and bought a smoke ball on

the strength of it. She had followed the instructions to the letter, and yet now – as their doctor could

confirm – she had flu.

There was no reply. But £100 was not a sum to be sneezed at. Mr. Carlill persisted. The company resisted.

Louisa recovered and sued. In June, Mr. Justice Hawkins found in Mrs. Carlill's favour. The company's

main defence was that adverts were mere "puffery" and only an idiot would believe such extravagant

claims. Judge Hawkins pointed out that adverts were not aimed at the wise and thoughtful, but at the

credulous and weak. A vendor who made a promise "must not be surprised if occasionally he is held to his

promise".

Carbolic appealed. In December, three lord justices considered the case. Carbolic's lawyers tried several

lines of defence. But in the end, the case came down to a single matter: not whether the remedy was

useless, or whether Carbolic had committed fraud, but whether its advert constituted a contract – which

the company had broken. A contract required agreement between two parties, argued Carbolic's lawyers.

What agreement had Mrs. Carlill made with them?

There were times, the judges decided, when a contract could be one-sided. The advert had made a very

specific offer to purchasers: protection from flu or £100. By using the smoke ball as instructed, Mrs.

Carlill had accepted that offer. The company might just have wriggled out of it if it hadn't added the

bit about the £1,000 deposit. That, said the judges, gave buyers reason to believe Carbolic meant what

it said. "It seems to me that if a person chooses to make extravagant promises of this kind, he probably

does so because it pays him to make them, and, if he has made them, the extravagance of the promises is

no reason in law why he should not be bound by them," pronounced Lord Justice Bowen.

Louisa got her £100. The case established the principle of the unilateral contract and is frequently

cited today.

Communicating Styles and Conflict

Drag heading here for Section

A

A As far back as Hippocrates' time (460-370 BC), people have tried to

understand other people by characterizing them according to personality type or temperament. Hippocrates

believed there were four different body fluids that influenced four basic types of temperament. His work

was further developed 500 years later by Galen. These days there are a number of self-assessment tools

that relate to the basic descriptions developed by Galen, although we no longer believe the source to be

the types of body fluid that dominate our systems.

Drag heading here for Section

B

B The values in self-assessments that help determine personality style.

Learning styles, communication styles, conflict-handling styles, or other aspects of individuals is that

they help depersonalize conflict in interpersonal relationships.

The depersonalization occurs when you realize that others aren't trying to be difficult, but they need

different or more information than you do. They're not intending to be rude: they are so focused on the

task they forget about greeting people. They would like to work faster but not at the risk of damaging

the relationships needed to get the job done. They understand there is a job to do. But it can only be

done right with the appropriate information, which takes time to collect.

When used appropriately, understanding communication styles can help resolve conflict on teams. Very

rarely are conflicts true personality issues. Usually they are issues of style, information needs, or

focus.

Drag heading here for Section

C

C Hippocrates and later Galen determined there were four basic temperaments:

sanguine, phlegmatic, melancholic and choleric. These descriptions were developed centuries ago and are

still somewhat apt, although you could update the wording. In today's world, they translate into the

four fairly common communication styles described below:

Drag heading here for Section

D

D The sanguine person would be the expressive or spirited style of

communication. These people speak in pictures. They invest a lot of emotion and energy in their

communication and often speak quickly. Putting their whole body into it. They are easily sidetracked

onto a story that may or may not illustrate the point they are trying to make. Because of their

enthusiasm, they are great team motivators. They are concerned about people and relationships. Their

high levels of energy can come on strong at times and their focus is usually on the bigger picture,

which means they sometimes miss the details or the proper order of things. These people find conflict or

differences of opinion invigorating and love to engage in a spirited discussion. They love change and

are constantly looking for new and exciting adventures.

Drag heading here for Section

E

E The phlegmatic person – cool and persevering – translates into the

technical or systematic communication style. This style of communication is focused on facts and

technical details. Phlegmatic people have an orderly methodical way of approaching tasks, and their

focus is very much on the task, not on the people, emotions, or concerns that the task may evoke. The

focus is also more on the details necessary to accomplish a task. Sometimes the details overwhelm the

big picture and focus needs to be brought back to the context of the task. People with this style think

the facts should speak for themselves, and they are not as comfortable with conflict. They need time to

adapt to change and need to understand both the logic of it and the steps involved.

Drag heading here for Section

F

F The melancholic person who is soft-hearted and oriented toward doing things

for others translates into the considerate or sympathetic communication style. A person with this

communication style is focused on people and relationships. They are good listeners and do things for

other people – sometimes to the detriment of getting things done for themselves. They want to solicit

everyone's opinion and make sure everyone is comfortable with whatever is required to get the job done.

At times this focus on others can distract from the task at hand. Because they are so concerned with the

needs of others and smoothing over issues, they do not like conflict. They believe that change threatens

the status quo and tends to make people feel uneasy, so people with this communication style, like

phlegmatic people need time to consider the changes in order to adapt to them.

Drag heading here for Section

G

G The choleric temperament translates into the bold or direct style of

communication. People with this style are brief in their communication – the fewer words the better.

They are big picture thinkers and love to be involved in many things at once. They are focused on tasks

and outcomes and often forget that the people involved in carrying out the tasks have needs. They don't

do detail work easily and as a result can often underestimate how much time it takes to achieve the

task. Because they are so direct, they often seem forceful and can be very intimidating to others. They

usually would welcome someone challenging them. But most other styles are afraid to do so. They also

thrive on change, the more the better.

Drag heading here for Section

H

H A well-functioning team should have all of these communication styles for

true effectiveness. All teams need to focus on the task, and they need to take care of relationships in

order to achieve those tasks. They need the big picture perspective or the context of their work, and

they need the details to be identified and taken care of for success.

We all have aspects of each style within us. Some of us can easily move from one style to another and

adapt our style to the needs of the situation at hand-whether the focus is on tasks or relationships.

For others, a dominant style is very evident, and it is more challenging to see the situation from the

perspective of another style.

The work environment can influence communication styles either by the type of work that is required or by

the predominance of one style reflected in that environment. Some people use one style at work and

another at home.

The good news about communication styles is that we have the ability to develop flexibility in our

styles. The greater the flexibility we have, the more skilled we usually are at handling possible and

actual conflicts. Usually it has to be relevant to us to do so, either because we think it is important

or because there are incentives in our environment to encourage it. The key is that we have to want to

become flexible with our communication style. As Henry Ford said, "Whether you think you can or you

can't, you're right!"